Twenty Years After 9/11, Lila Nordstrom Is Still Fighting for Survivor Health Care Rights

[ad_1]

Lila Nordstrom was a 17-year-old high school senior at Stuyvesant High School when she watched the Twin Towers fall 20 years ago from her classroom window. Assured by local officials and then Environmental Protection Agency administrator Christine Todd Whitman that the air quality was safe, Nordstrom and her classmates returned to school on October 9, 2001. But as she watched cleanup operation ceremony parades outside the classroom windows, she describes a feeling of “inherent paranoia” among her and her classmates. “Loud noises became very threatening,” she says. “The whole class would fall apart if there was one loud noise.”

Five years later, one of Nordstrom’s classmates was diagnosed with cancer and believed it to be 9/11-related. Then NYPD officer James Zadroga died of a respiratory illness that was definitively linked to his work in the disaster cleanup. Nordstrom, then 21, was graduating college and about to lose access to health care. She realized that she and her classmates had also been exposed in the 9/11 aftermath: “And we’re going to get sick too.”

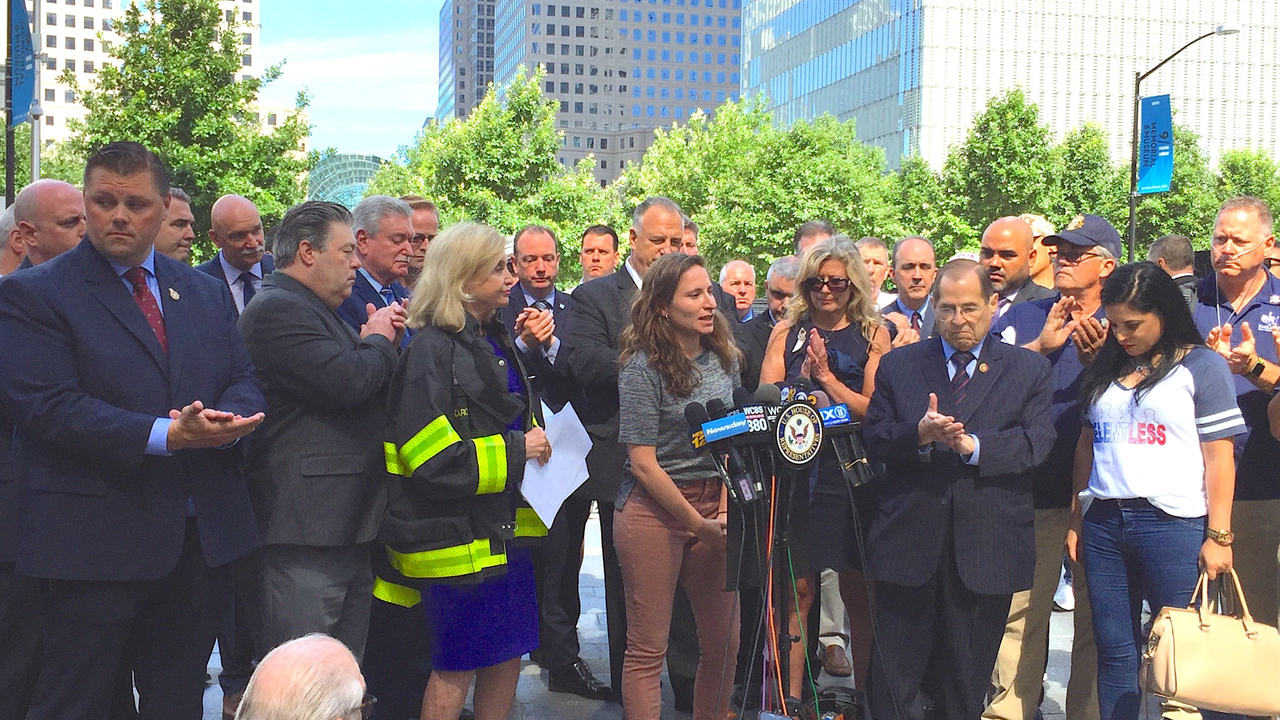

It was the call to action Nordstrom needed. In 2006 she created StuyHealth, an advocacy group to represent the young adults present during the 9/11 cleanup, and went to D.C. to lobby for the Victim Compensation Fund the following year. Nordstrom had experience talking to politicians—when she was growing up, her mom had taken her to local representatives’ offices, so she knew she could be heard without being invited. But on the Hill, Nordstrom found she wasn’t taken seriously.

“As a woman on the Hill, people don’t expect you to have information,” says Nordstrom. “They expect you to be a wife or a child. Plus, I looked 16 when I was 22. I looked like someone’s intern.” She trained the other advocates working with her to echo what she said every time she spoke. “It’s like improv. You have to do what you need to do to be heard.”

Now, at 37 and with over a decade spent fighting for health care rights, Nordstrom documents the challenges of being a young woman in an advocacy space primarily dominated by older men in her new memoir, Some Kids Left Behind: A Survivor’s Fight for Health Care in the Wake of 9/11, out this year. She has been advocating for the survivor community since 2007—and this book is the next step in that journey. “The story of the 9/11 survivor community isn’t well understood,” Nordstrom says. “I also wanted to create a road map to show other communities and young advocates that they can and should demand change.”

According to Nordstrom, one of the biggest hurdles she faced was getting data. Medical research funding is expensive, and 90% of the 9/11 first responders were male—meaning women were extremely underrepresented in the physical health studies conducted in the aftermath of the disasters. The James Zadroga 9/11 Health and Compensation Act of 2010 does provide a health care program for 9/11 first responders and survivors. But, as Nordstrom points out, “if your condition isn’t affirmatively linked to 9/11, you can’t get into the program.” Because the only population they have to draw those distinctions from is the first responders, that means women, young people, and others impacted by 9/11 may have a more difficult time accessing the program. “Likely linked women’s health conditions, like infertility and uterine cancers, are not covered by the Zadroga Act federal program,” she adds.

Nordstrom says that mental health care coverage—vital for 9/11 survivors—has also been an insurance red tape nightmare. “The [Zadroga Act federal] program acts as a second payer for us and a primary payer for responders.” So when Nordstrom saw a psychiatrist, for example, his office couldn’t use a second payer for payment (as most mental health providers won’t do). She says she had to stop seeing him. She also pays $400 a month for health insurance, which she must have to be part of the World Trade Center Health Program. “There’s no system for people who don’t have access to the program, which is disproportionately women and young people,” says Nordstrom.

[ad_2]

Source link